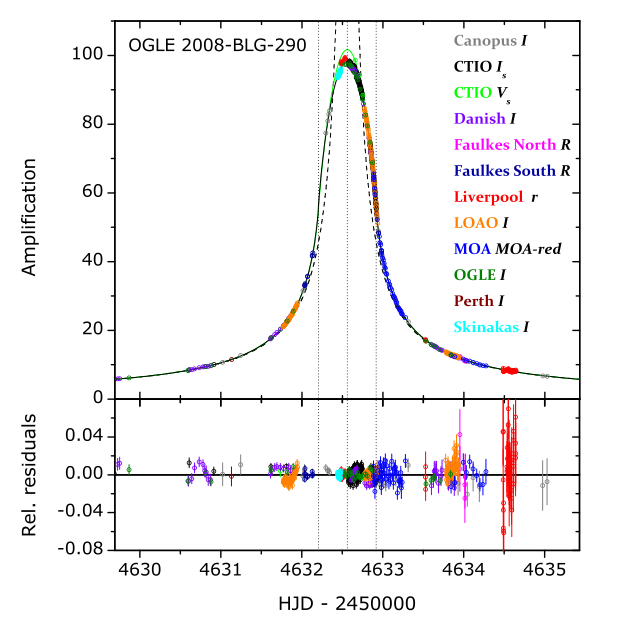

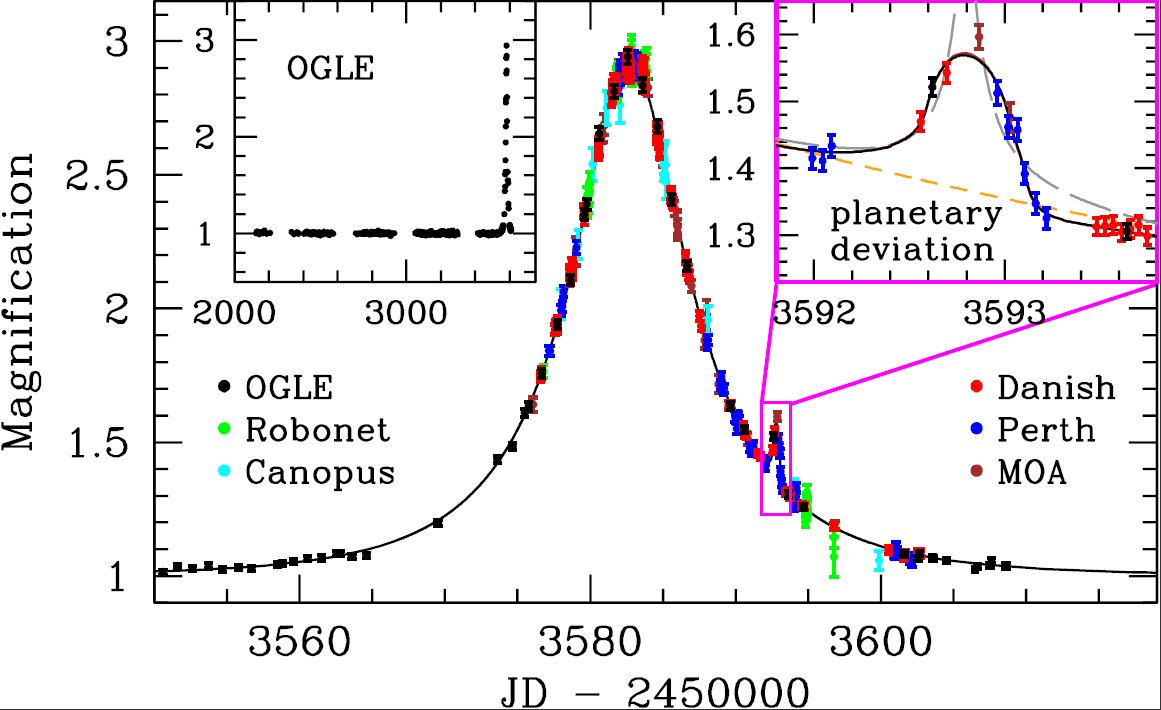

Figure 1 taken from Fouque et al., A&A 518, 51 (2010)

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

The basic theory of gravitational lensing is pretty easy to find. I have a few pages on it from previous courses.

So, in the simplest case of a single star lensing a more distant single star, we can learn quite a bit about the masses and motions of the stars. We can even, sometimes, "see" details in the atmosphere of the lensed star -- such as limb darkening:

Figure 1 taken from

Fouque et al., A&A 518, 51 (2010)

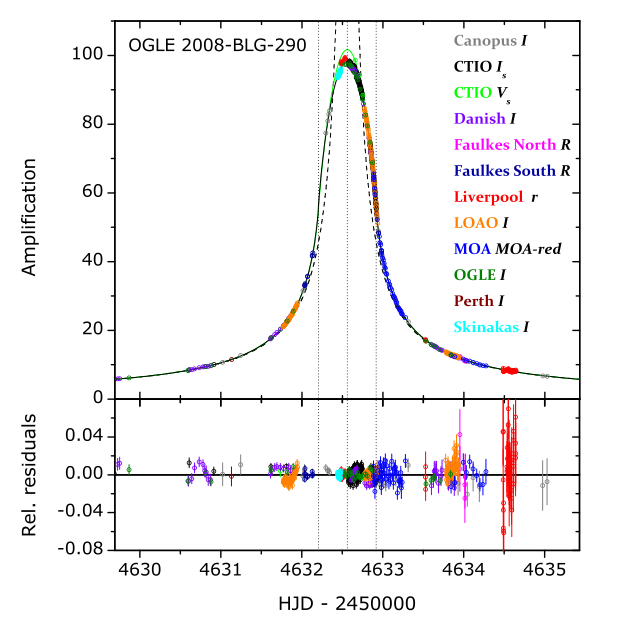

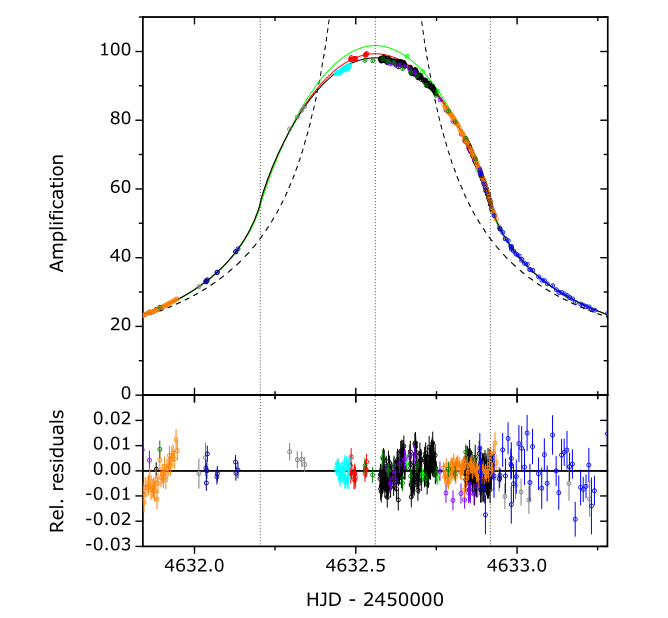

Figure 2 taken from

Fouque et al., A&A 518, 51 (2010)

But how can lensing help us to find planets?

Let's summarize the basic properties of gravitational lensing, as they pertain to finding planets around other stars using this technique.

The Good The Bad

------------------------------------------------------------------

can reveal very low-mass rare, requires millions

objects of measurements

can work on systems at does not yield direct value

very large distances of mass (without additional

from the Earth information from other

methods)

requires teams of observers

around the world

not repeatable

------------------------------------------------------------------

That last one is a doozy. If only one group was able to observe an event, there's no real way to check it afterwards to verify that it wasn't an artifact of some sort.

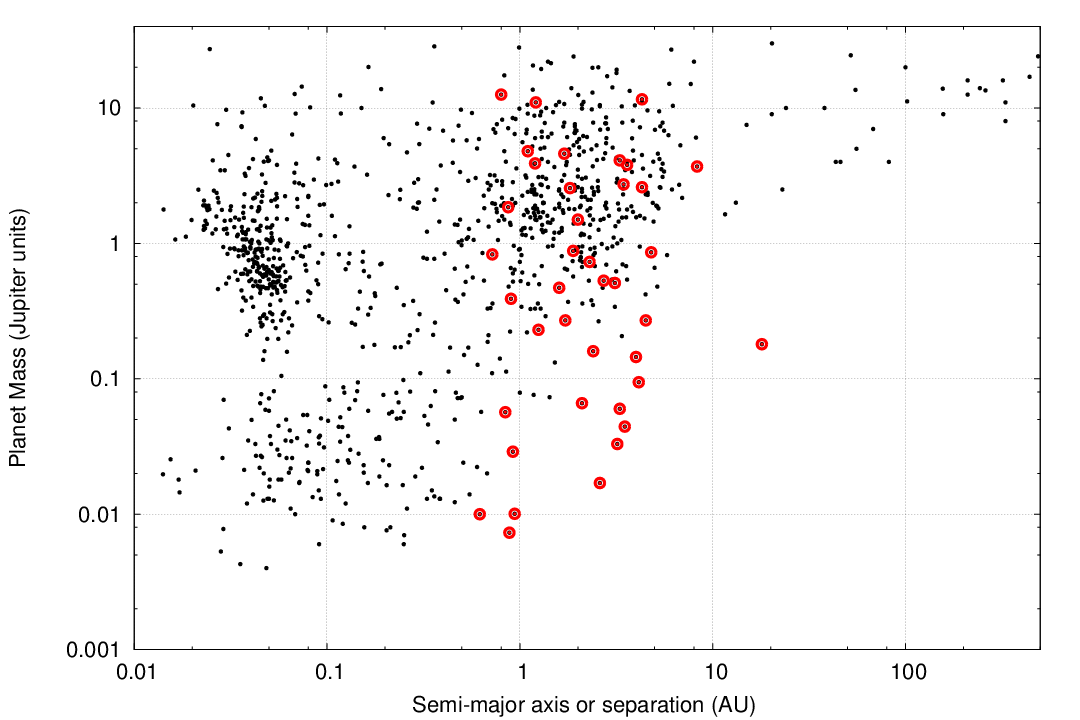

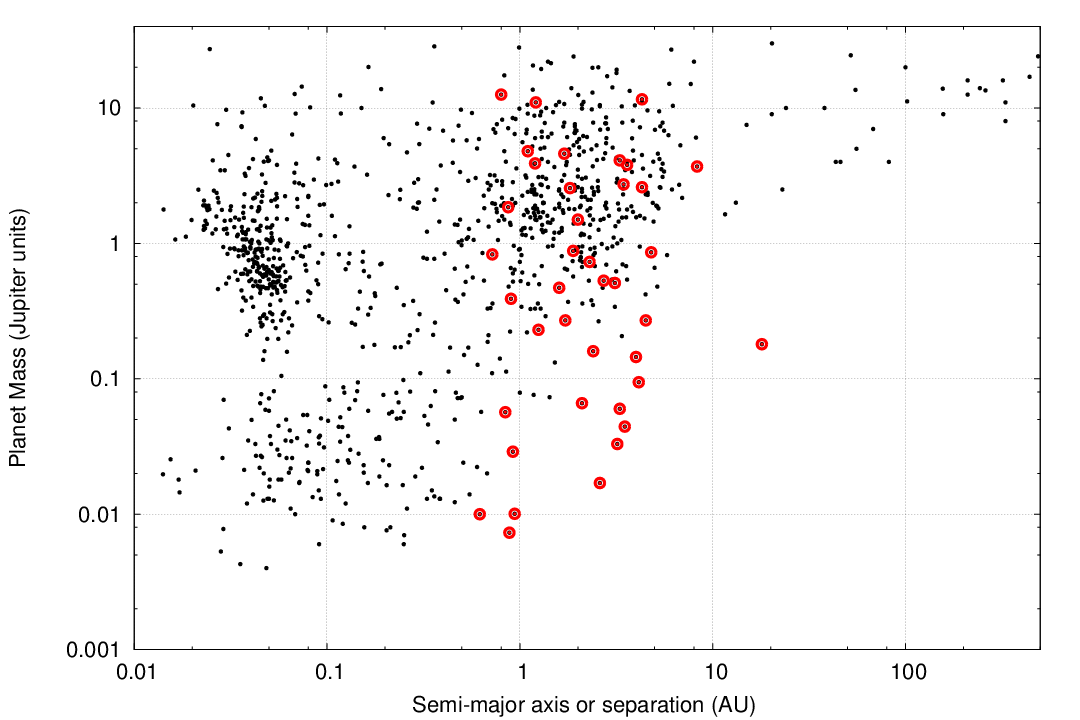

Let's take a look at the current census of exoplanets to see how many have been discovered via gravitational lensing, and what their properties might be.

This is actually just a subset of all the exoplanets which have been detected via lensing. Some of the detections have not provided unambiguous values for the separation or mass.

In 2005, three big collaborations joined forces in order to collect very detailed measurements of a microlensing event which turned out to include a low-mass planet. Let's look at this in some detail. You can find a wealth of information at

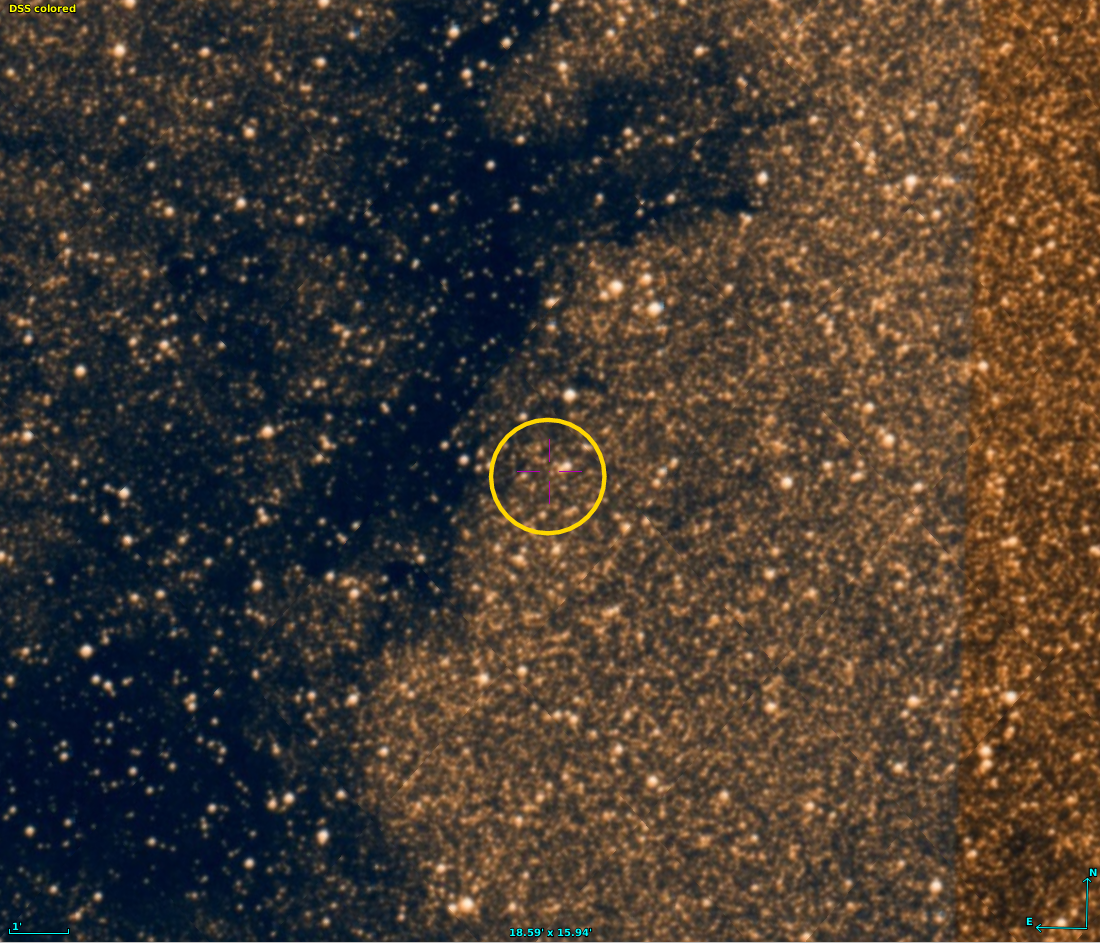

The star is located in the direction of the bulge of the Milky Way -- hence the BLG part of its name. The Optical Gravititional Lens Experiment (OGLE) team had been monitoring this field for years. It lies in a "window" near the center of the galaxy, where the dust clouds are less dense than usual.

Image thanks to Google Sky

If we zoom into a region just 10x10 arcminutes on a side, we find, well, a LOT of stars. It's a good place to look for rare microlensing events, because one can see and monitor tens or hundreds of thousands of stars all at once.

An even closer view shows the star itself clearly. It's nothing special.

Image courtesy of

the PLANET collaoration

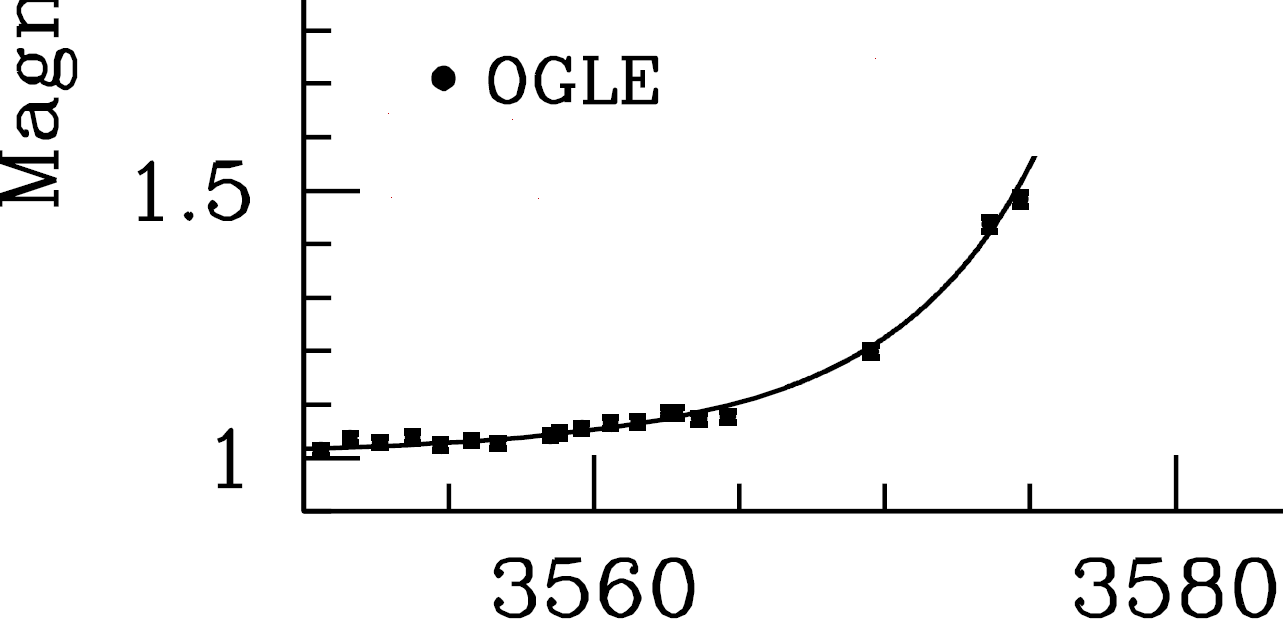

But, early in the 2005 observing season, the OGLE team noticed that this non-descript little star was growing brighter and brighter, day after day. They sent out a message using their Early Warning System, alerting the other groups that a microlensing event was starting to take place.

Image modified from original at

Discovery of OGLE 2005-BLG-390Lb, the first cool rocky/icy exoplanet

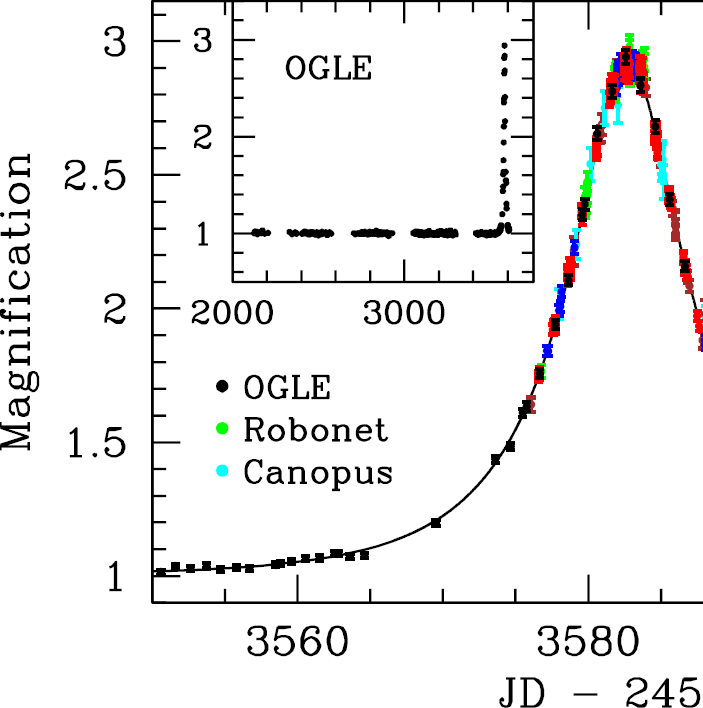

At this point, the other groups jumped into action. They, too, started pointing their telescopes at the field and making measurements every night, or several times a night.

Q: Why didn't we (here at RIT) join them?

The star reached a peak brightness of about 3 times its usual intensity, then started to fade. So far, it looked like a garden-variety microlensing event: a foreground lens star was passing in front of a background source star.

Image modified from original at

Discovery of OGLE 2005-BLG-390Lb, the first cool rocky/icy exoplanet

Let's watch a movie of the star, made some time after all the excitement was over. Click on the image to watch the movie play.

A-HA! Did you catch it? As it was fading back to its ordinary level, the star very briefly flashed out light.

Image at

Discovery of OGLE 2005-BLG-390Lb, the first cool rocky/icy exoplanet

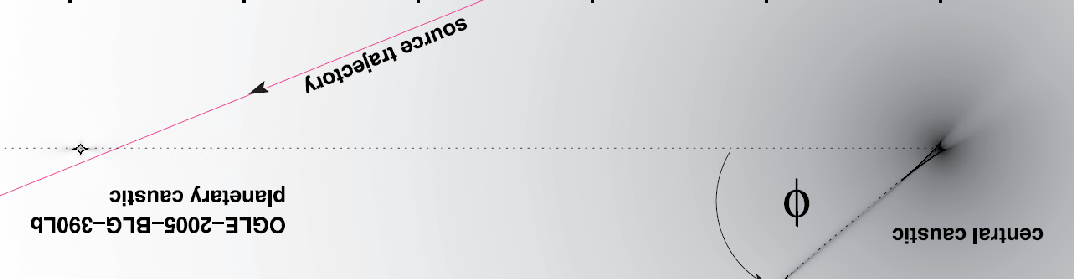

What happened was that there was a planet orbiting the lensing star, and as the source star drifted past the lensing star, it went directly behind a caustic of the star-planet lens. Click on the image to see a movie of the event.

In this system, the star is roughly 13,000 times more

massive than the planet.

Q: What is the ratio of the Einstein-ring radius of the planet

to that of the star?

Q: Could you see the Einstein ring of the planet on this diagram?

Q: What is the impact parameter bs of the

background source, measured in terms of the STAR's

Einstein ring radius?

Q: Do you expect to see any significant lensing due to the

lensing star in this case?

Q: What is the impact parameter bp of the

background source, measured in terms of the PLANET's

Einstein ring radius?

Q: Do you expect to see any significant lensing due to the

lensing planet in this case?

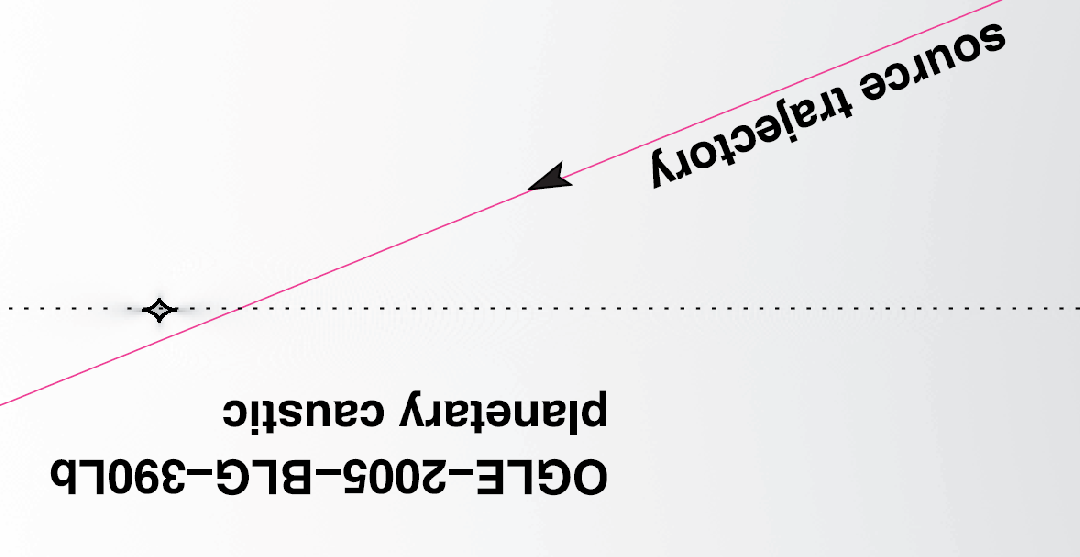

What's a caustic? It's, uh, rather complicated mathematically to compute. The basic idea is that the interaction of the gravitational bending due to the lensing star, and the lensing planet nearby, produces a small region in which the lensing effect is very powerful.

For example, in the case of OGLE-BLG-390, Kubas et al., A&A 483, 317 (2008) have calculated that the caustic region looks like this:

Image taken and mangled from

Kubas et al., A&A 483, 317 (2008)

Image taken and mangled from

Kubas et al., A&A 483, 317 (2008)

That funny diamond-shaped region is the caustic. It lies directly on the line between the lensing star and the lensing planet; in this particular case, it happens to be roughly at the Einstein radius of the star, but that's a coincidence (I think).

Now, here's the important thing about caustics.

Q: Does this increase the chances of seeing an event due

to the planet?

Q: Does this increase the chances of seeing an event due

to the planet?

Okay, back to the case of OGLE-BLG-390. Let's watch the lensing effects in action in this nice movie made by Andrew Williams and David Bennett. Click on the picture to start the movie.

So, what did we learn in this case? It turns out that the planet's mass was much smaller than the star's mass. Gravitational lensing analysis doesn't directly yield the mass of either object, but it can tell us the ratio:

-5

mass(planet) = 7.6 x 10 mass(star)

Q: The statistics of stellar populations in the bulge

suggest that the lensing star is a red dwarf

with mass of about 0.2 solar.

What is the mass of the planet?

We don't know the distance to the lensing system, either, but an analysis of the relative motion of the lensing system to the background star, taking into account the typical galactic motions of objects in that direction, yields an estimate that D ~ 6 kpc.

Pretty good, huh? Detecting a planet not much more massive than the Earth, more than halfway to the center of the Milky Way ....

The experts have derived many other likely properties for the planet and its star. Take a look at Oodles of detailed information on the event OGLE 2005-BLG-390 and references therein for all the details.

Let's look again at the properties of all the planets which have been discovered by microlensing, now that we know a bit more about how the process works.

In 2004, An et al., ApJ 601, 845 (2004) noticed a small anomaly in the light curve of a microlensing event in the Andromeda Galaxy. They were monitoring M31 because it, like the center of the Milky Way, is a good place to find lots and lots of stars, all close together.

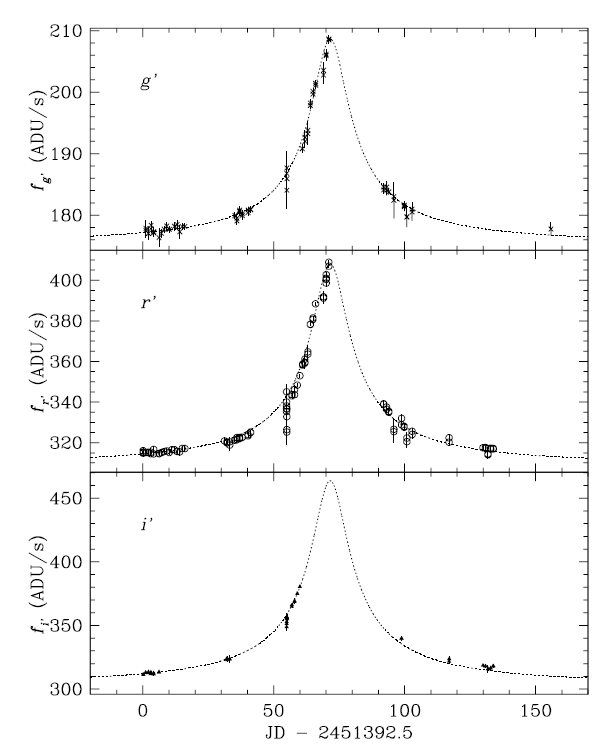

Figure 1 from

An et al., ApJ 601, 845 (2004)

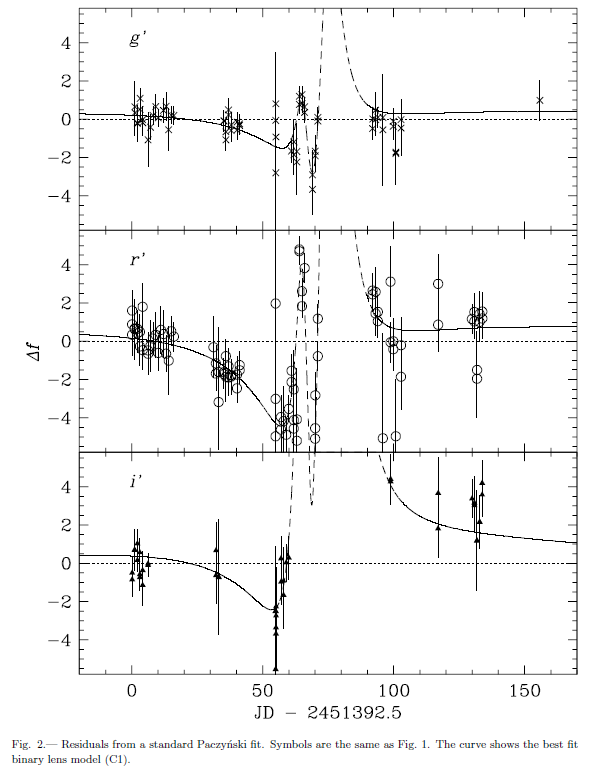

Note the little "notch" near the start of the event. If you fit a simple point-lens model to the light curve and subtract it from the data, you are left with a residual which looks like this:

Figure 2 from

An et al., ApJ 601, 845 (2004)

If one fits a binary lens model -- star plus less-massive-object -- to the residuals, one finds that the second object must be considerably less massive than the first. It's all rather ambiguous, since we don't know WHERE the lensing system really is.

The ambiguity in distance leads to a large range of possible masses for the lensing star and the secondary lensing object. It is possible that the secondary object might be as little as 6 times the mass of Jupiter.

There are three big teams involved in the search for planets via microlensing:

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.