You are familiar with waves created by a piston moving through water:

You can perceive electromagnetic waves with your eyes. One way to create them is to wiggle a charged electric particle: the frequency of its oscillation will be the frequency of the light wave it emits.

Java applet from the excellent

NTNUJAVA Virtual Physics Laboratory

site. Thanks!

It turns out that two massive objects moving rapidly around each other will create gravitational waves, ripples in the very fabric of space itself.

Movie of black hole binary inspiral courtesy of

the SXS project.

Gravitational waves have some very interesting properties. For example, when they pass through a region, they "squeeze" the space in that region in alternating directions: first it expands horizontally while contracting vertically, then contracts horizontally while expanding vertically.

If we put a painting on that wall through which the wave passes, we might see it distort sort of like this:

There's just one problem: even the most massive, rapidly moving objects in the sky -- binary black holes orbiting around each other every few minutes or hours -- produce gravitational waves with small amplitudes. Really small amplitudes. Really, really, REALLY SMALL AMPLITUDES.

How small? Physicists can describe the amplitude of a gravitational wave with a fraction: how much longer (or shorter) does an object become when the wave passes through it? For example,

Example: Joe waves his magic wand and creates

a gravitational wave with an amplitude

of A = 10 percent = 0.1. The wave moves

towards his little brother Billy,

who is H = 1.2 meters tall

under ordinary circumstances.

How tall will Billy be when the

wave is passing through him?

A gravitational wave of that amplitude would be easy to detect.

Unfortunately, the real gravitational waves generated by astrophysical objects aren't quite that strong. For example, the amplitude of the wave created by a pair of neutron stars if they were to spiral into each other at a distance of about 20 Mpc (that's roughly the distance of the nearest cluster of galaxies) is about

-20

A = 10

Q: Joe holds a meter stick in front of him

and measures it very carefully.

If a gravitational wave with this

amplitude were to pass through

the meter stick, how much longer

would it grow?

Just how easy would it be to

detect this sort of change in length?

The answer is: really, really hard. For reference, here are some sizes of objects you might try to use in the measurement procedure.

Golly. Is there ANY way to detect a gravitational wave?

(Note: much of the following material is shamelessly taken from Alan Weinstein's 2006 lectures on gravitational waves and LIGO, which can be found at the Undergraduate Resources section of the the main LIGO web site.

The Michelson interferometer is a device which splits a single beam of light into two beams. It sends each beam down a long tunnel and back using mirrors, the two beams travelling in perpendicular directions. Then the beams are brought back together so that they can interfere with each other.

LIGO -- the Laser Interferometry Gravitational wave Observatory -- has two of these interferometers. One is in Hanford, Washington, and other in Livingston, Lousiana.

At each site, there are tunnels about 4 km long running in perpendicular directions.

A gravitational wave with an amplitude of

-20

A = 10

passes through the Earth near the Hanford

LIGO site. It happens to run vertically

down into the Earth's surface, so that

its distortion first makes one leg longer

and then other other leg longer.

Q: How large is the difference in

distance travelled by light going

along the North leg, compared

to the light going along the East leg?

Just how easy would it be to

detect this sort of change in length?

This is a REALLY tough engineering job.

There were some problems ...

... but things are going very well now. LIGO has been gathering data for several years. It's not the only gravitational wave observatory, either: scientists in other countries have built their own.

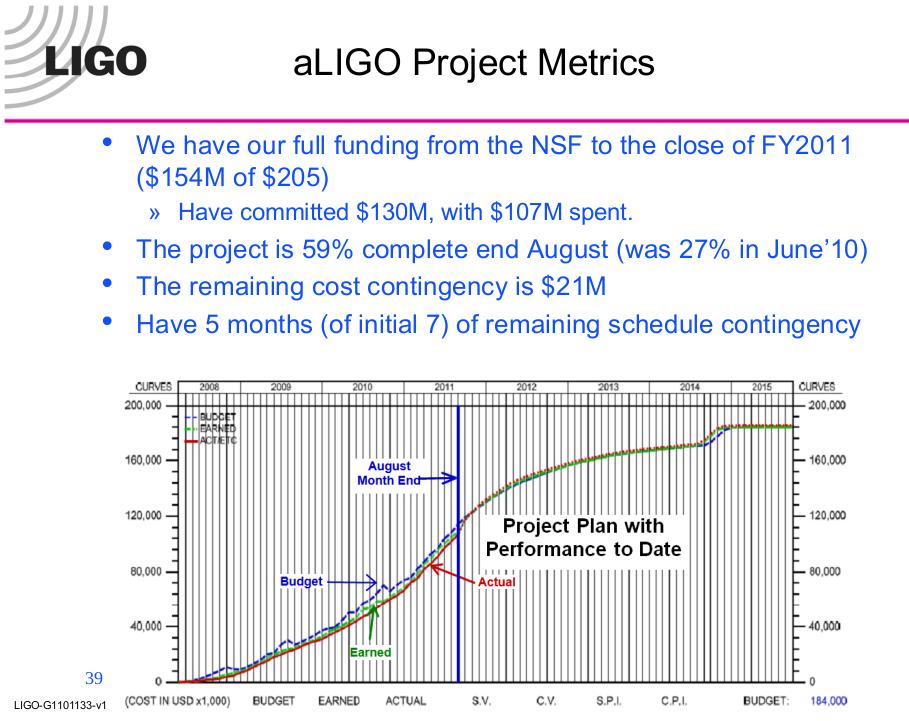

Much of the following is taken from a presentation by David Shoemaker for the ICATPP meeting in October, 2011.

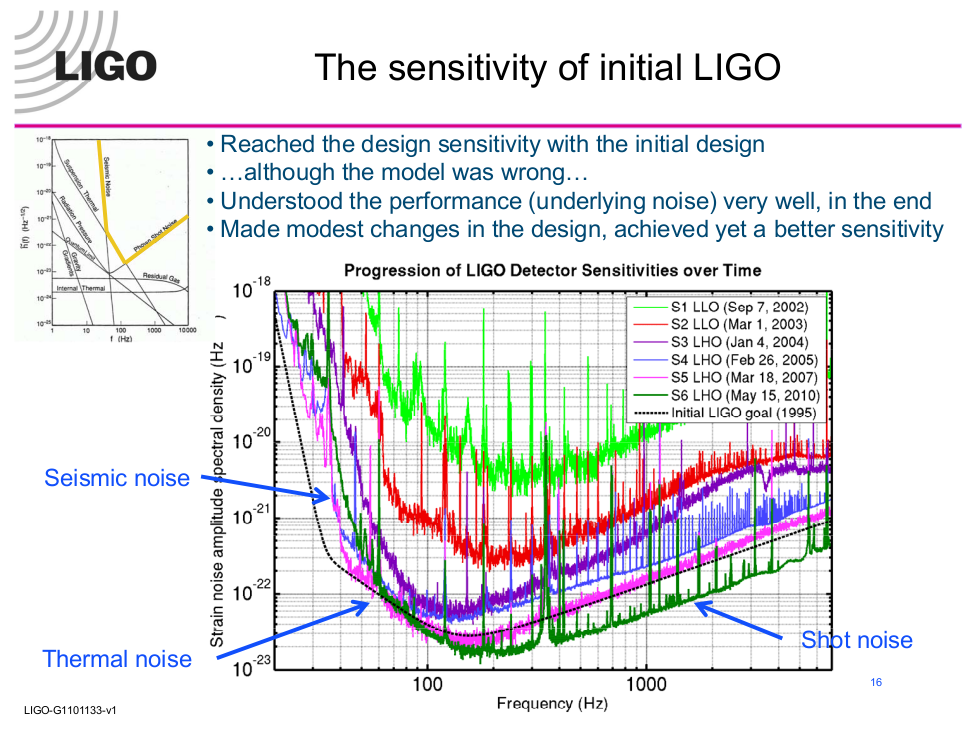

The initial version of LIGO does meet the specifications for sensitivity:

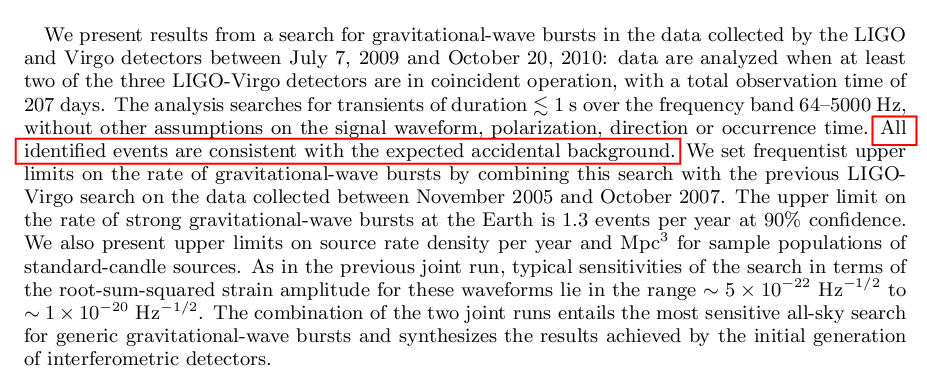

Between July 7, 2009, and October 20, 2010, the LIGO and Virgo detectors observed the sky and recorded huge amounts of information. A large group of scientists has searched this dataset for signs of gravitational waves. Their conclusion?

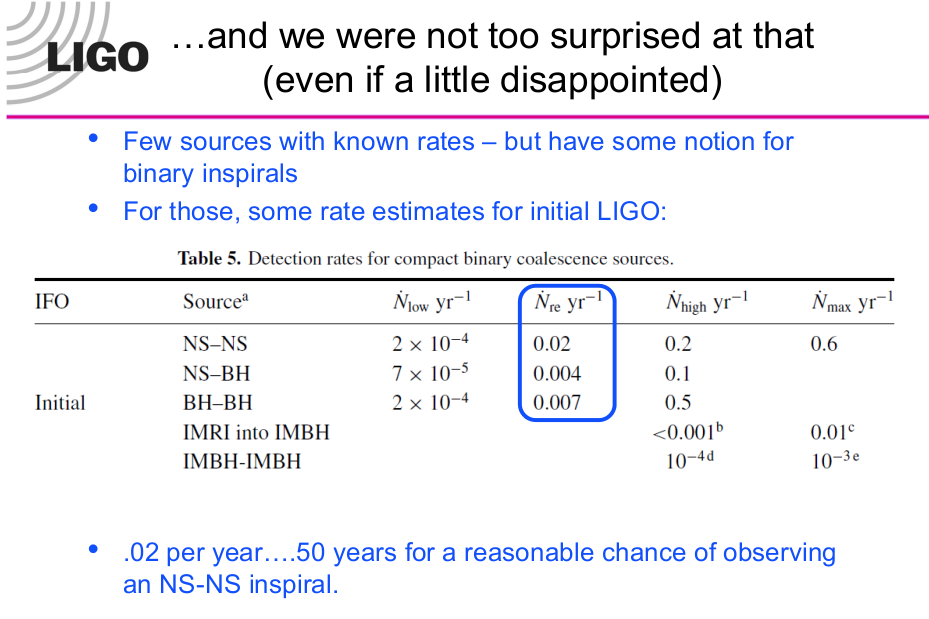

But then again, when scientists try to figure out how many sources they OUGHT to see -- based on the sensitivity of the detectors and the number and distances of known gravitational wave sources, like binary black holes and neutron stars, this null result is exactly what they expect.

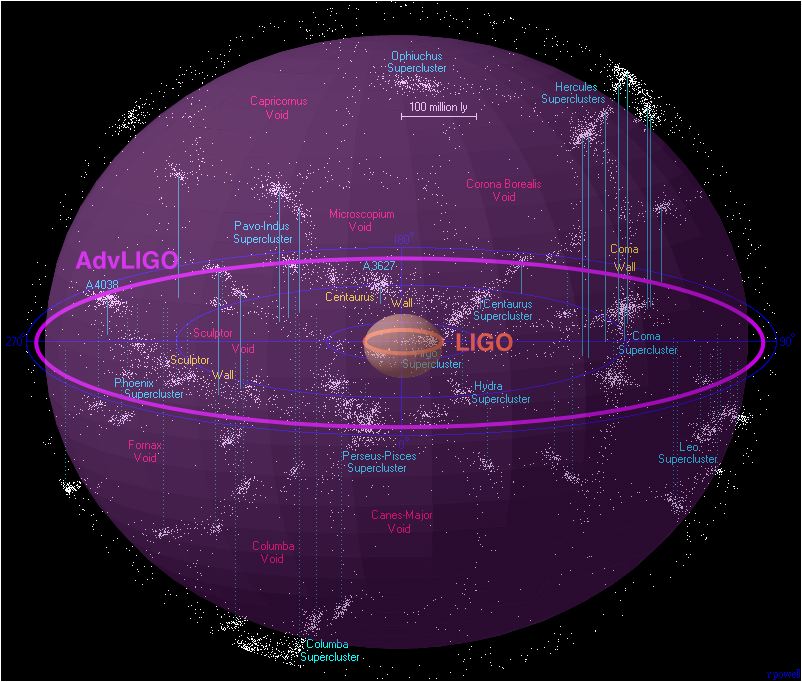

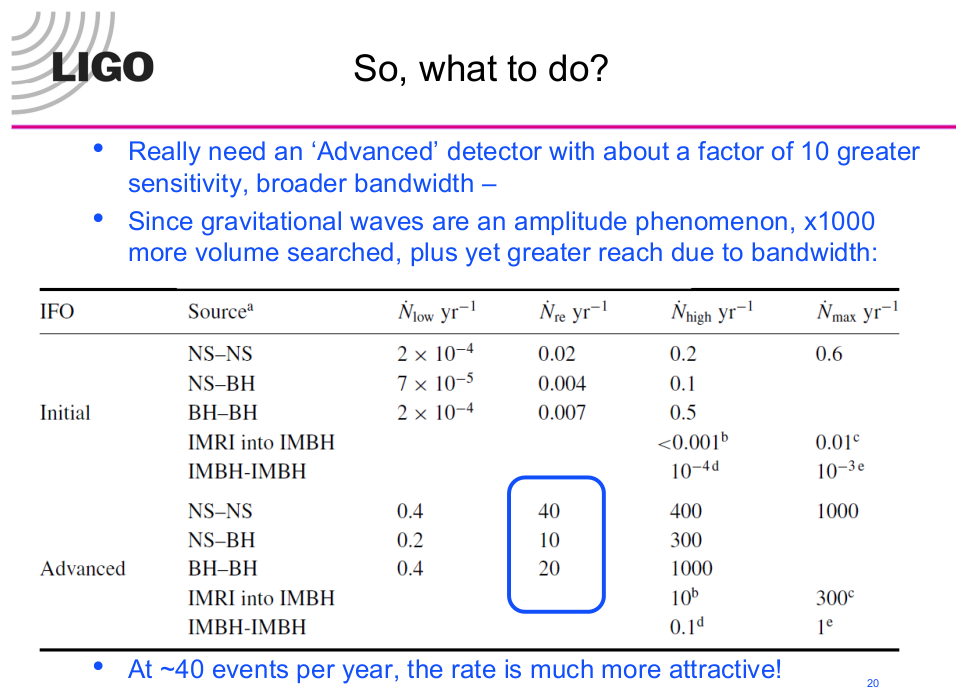

However, if the detectors were just 10 times more sensitive, they would probe a volume of space 10*10*10 = 1000 times larger

which would increase the number of expected events per year to reasonable levels.

And so, LIGO is becoming "Advanced LIGO". It will take some time and money ....