Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

What DOES all this eigen-stuff have to do with the motion of two coupled oscillators?

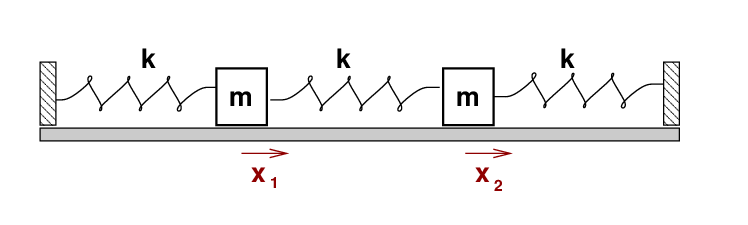

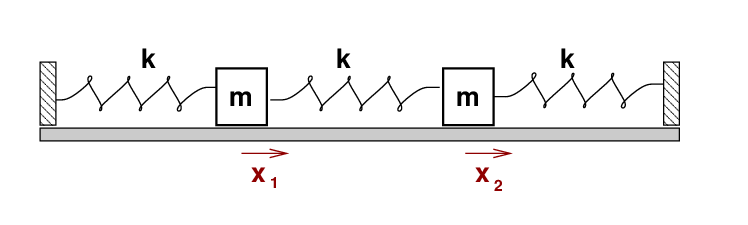

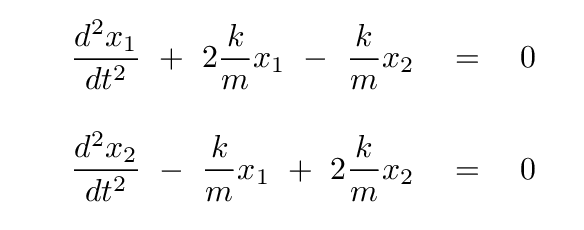

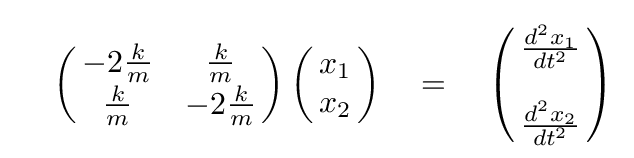

Quite a bit. Recall, please, the equations we derived a short time ago describing the forces on two identical blocks which are connected by three identical springs.

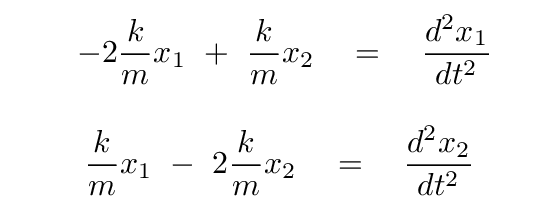

Well, suppose that we re-arrange the terms in this equation just a bit, putting the derivatives over on the right-hand side.

Doesn't this look a bit like a matrix equation? In particular, like THIS matrix equation?

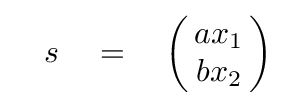

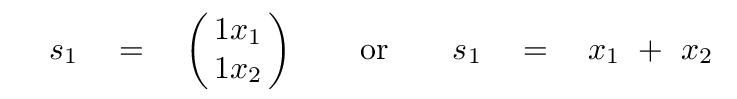

Now, this next step is the crucial one. What we need to do is to combine the the real-life positions of the blocks, x1 and x2, in just the right mix. Let us define a new coordinate s which has exactly the right combination, mixing "a" parts of x1 with "b" parts of x2.

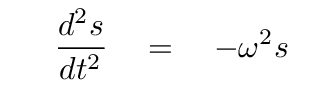

If we pick just the right mixture, we'll end up with a situation in which the second derivative with respect to time of this new coordinate is

In that case, our equations connecting forces and accelerations can be written

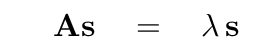

And that is simply the equation for the eigenvector s and eigenvalue λ = - ω2 corresponding to a matrix A.

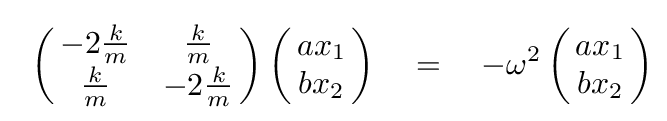

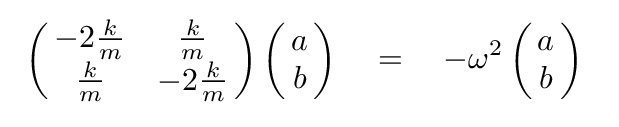

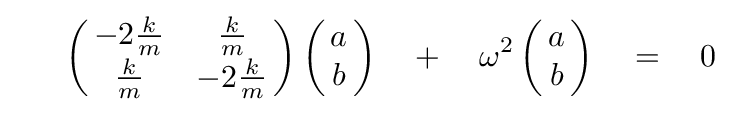

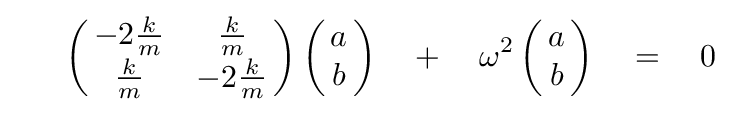

How to find this "just right" mixture of the block coordinates? All we have to do is to find the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the following matrix equation.

Let's do it!

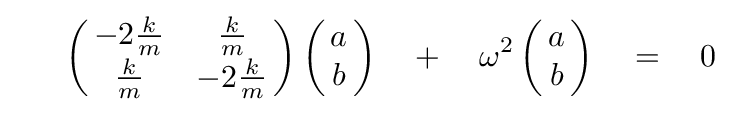

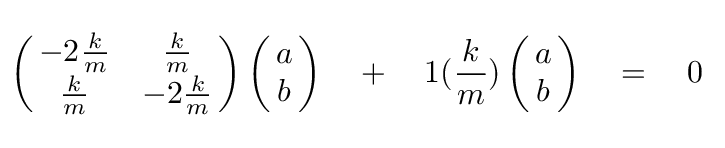

It will make things a bit easier if we move all the terms to the left-hand side.

Write down the two equations which result from performing

this matrix multiplication.

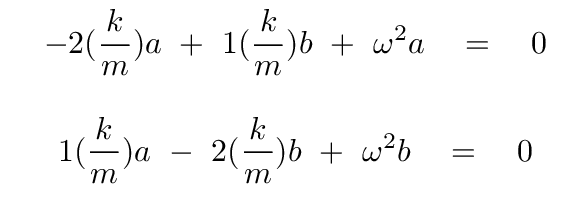

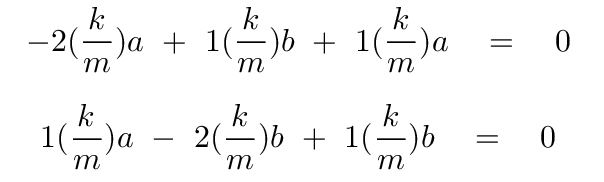

You should get

Just as we did earlier, we can solve these two equations for three unknowns to end up with the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of this equation.

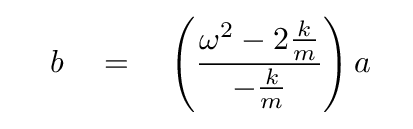

Use the first equation to solve for b in terms of a.

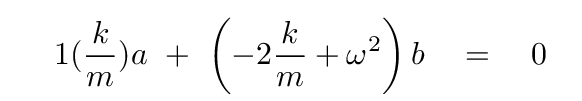

Now plug this into the second equation ...

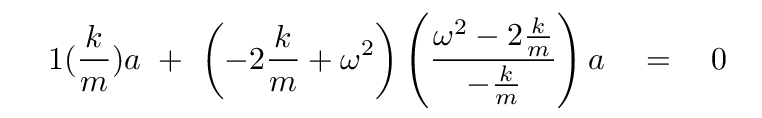

... to get

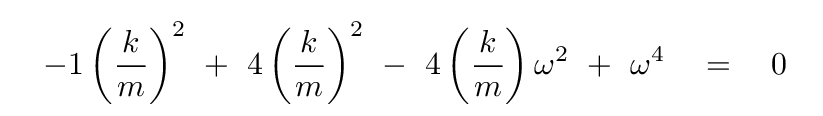

I know that looks bad, but actually, it simplifies quite a bit. Divide both sides by a, and after some algebra, you should find

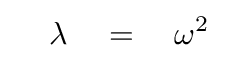

Hmmm. This is sort of like a quadratic equation, but the variable ω is raised to the fourth power. That's annoying. Let's make it more conventional by defining

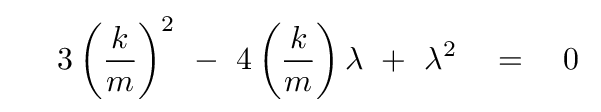

With this notation, the equation really is a simple quadratic

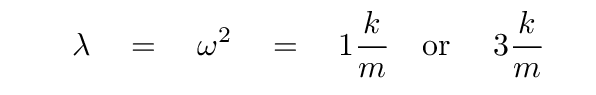

Q: What are the roots of this equation?

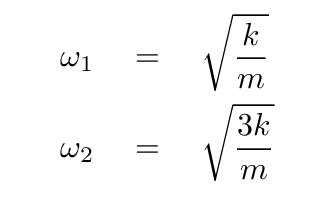

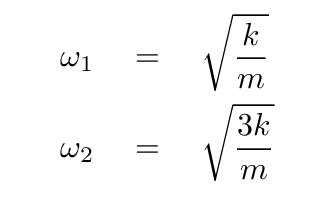

And so we see that the eigenvalues correspond to the frequencies of the normal modes.

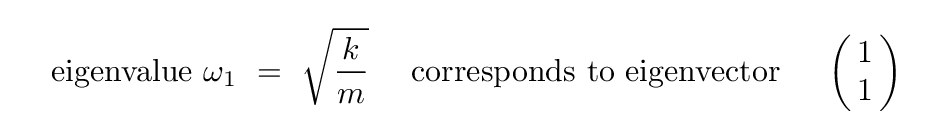

We're almost there now. Let's pick one of these eigenvalues, ω1 = √(k/m), and find its corresponding eigenvector.

To find the eigenvector, we insert an eigenvalue into those equations we derived earlier:

which yields

Now, perform the matrix multiplication, and you'll end up with two equations:

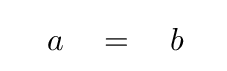

Q: Solve either of these equations for the variable a in terms of b

Each equation turns into

which means that

And the eigenvector tells us how to mix together the physical coordinates of the blocks x1 and x2 in order to find a combination which exhibits simple harmonic motion, with a frequency ω1 = √(k/m).

This special combination of the blocks' coordinates is sometimes called a normal coordinate, and the oscillations of this coordinate, which have a frequency given by one of the eigenvalues, are sometimes called normal modes of the system.

Let's pause for a moment to summarize the many, many calculations we've performed.

Got all that?

Good. Because our job isn't quite done.

We used the forces on the two blocks to write two equations, assumed that it would be possible to find normal modes of oscillations, and re-arranged things to yield

Our solution to the characteristic equation revealed that the two eigenvalues for this system were

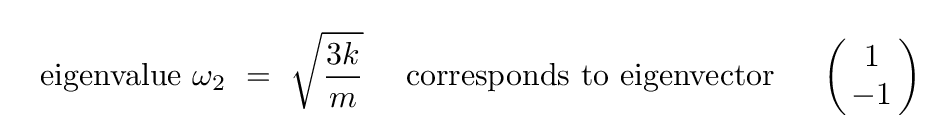

We've already computed the eigenvector for the first choice of frequency; but what about ω2?

Q: What is the eigenvector corresponding to ω2?

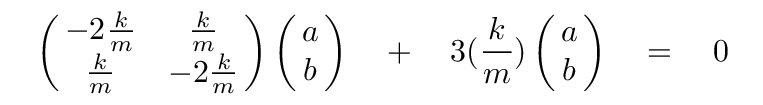

Well, plug that value into the two equations:

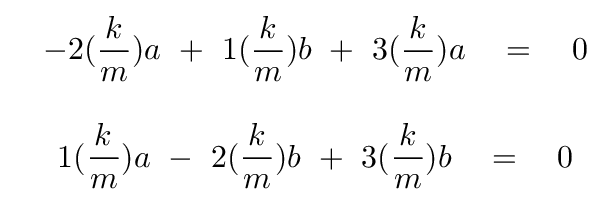

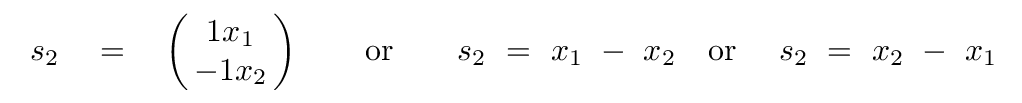

Do some algebra. You should find

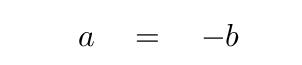

Pick one of these two -- it doesn't matter which. I'll choose the upper equation. Solve for a in terms of b.

And there you have it: in order to create the second eigenvector, we need to mix together 1 part of x1 with NEGATIVE 1 parts of x2.

In other words, to form the second eigenvector, we need to subtract one of the block coordinates from the other. Note that it doesn't matter which from which -- we can pick either possibility, and we'll still end up with the same motion.

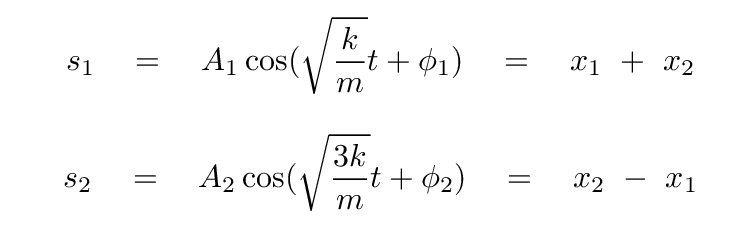

Great. You now know that the normal modes of this system are

Let's give you some additional information:

Where is the left-hand block at time t = 3 seconds? In other words, what is the value of x1 at t = 3?

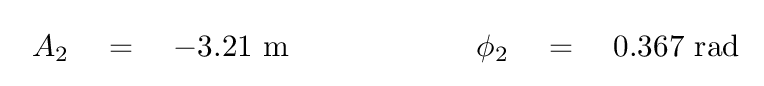

The first step is to deduce the four constants of integration, A1, A2, φ1, φ2 , by using the initial conditions. We find

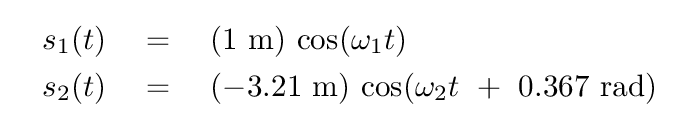

With this information, we can write the equations for each of the normal coordinates as a function of time.

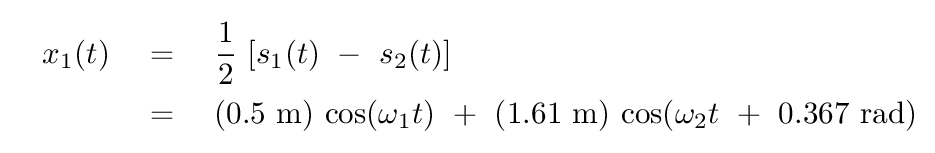

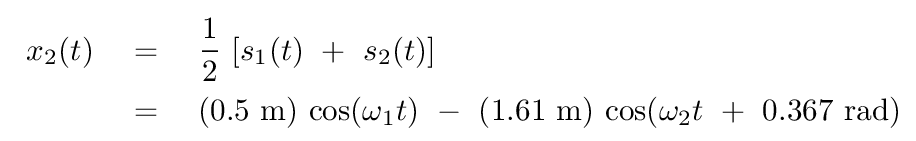

But if we want to know where the actual BOXES are, we need to figure out the values of x1 and x2 for any time. This requires just one more step. Our definitions of the normal coordinates defined them in terms of the real box coordinates: s1 = x1 + x2 and s2 = x2 - x1. If we turn these equations inside out, we can express each box' coordinate as a combination of the normal coordinates:

Phew. We can finally answer the question posed earlier: what is the position of the left-hand block at time t = 3 s? If we insert this time into our equation above, we find

at time t = 3 s, the left-hand block has position x1 = 0.71 m

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.