Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Finding the distance to a star can be done with trigonometry. Figuring out the size takes more work, but a combination of the inverse square law and the blackbody radiation equations gives us the size of a star relative to the Sun ... and we know the size of the Sun. But how can we measure the mass of a distant star?

It turns out that the only (good) way to measure stellar masses is to measure the properties of stars in binary systems. And the most useful such binaries are those in which the two stars take turns passing in front of each other, the eclipsing binary systems.

Way back in the seventeenth century, Johannes Kepler used Tycho Brahe's excellent observations of the planets to discover a simple relationship between the period of an orbit (P) and its radius (r):

2 3

P = a

Another way to write this is:

3

a

----- = const

2

P

It turns out that the constant in this equation is simply the total mass in the system. By "total mass", I mean "the mass of the two objects orbiting around each other."

Kepler studied planets orbiting the Sun. The mass of the Sun is so much larger than that of any planet that the total mass is pretty much just the mass of the Sun. But in the case of a pair of stars orbiting around each other, one must add the two masses together. Kepler's equation then becomes:

3

average separation

------------------------ = (total mass of stars)

2

Period of orbit

If one measures the period P in years, the separation a in Astronomical Units, then the total mass will be in solar masses.

So, all we have to do to measure the mass of a star (or a pair of stars) is to determine the period and size of their orbits around each other. But how can we do that?

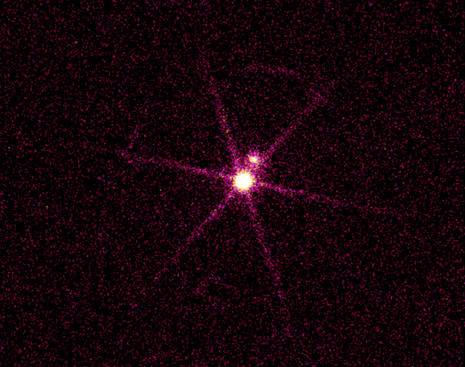

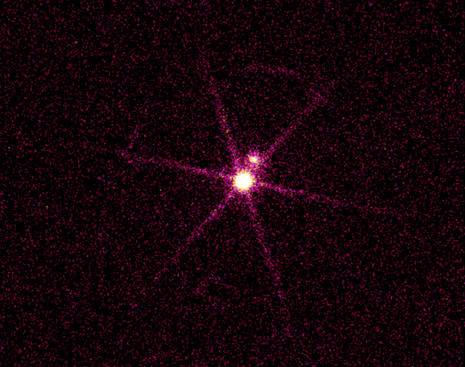

Some of these close pairs are just chance superpositions of a nearby star with a much more distant star, but others are bona fide binary systems in which the stars orbit around each other. If we wait long enough -- and it might take years or centuries -- we can see the two stars move around each other. Here's an example of a binary star observed by Hipparcos:

Q: What feature in this figure shows that

this star is one member of a binary system?

So, observations of a visual binary star can give us the period of the orbit, and also the apparent angular size of the orbit. Is that enough to calculate the mass of the two stars?

No!

Kepler's Law demands that we know the actual, physical size of the orbit, not the angular size. We need to know how many kilometers each star moves, not simply how many degrees. How can we turn angular measurements (like those shown on the Hipparcos graph) into real distances?

We need to know the distance L to the binary star system. We can then use the same old geometry you recall from parallax to calculate the physical distance B between two stars, given their angular separation theta.

But you may recall that it's difficult to measure precisely the distance to another star system. We can do a decent job only for the nearest few hundred stars. All the others are too far away for parallax to work ... which means that we can't use visual measurements of distant double stars to measure mass. Rats.

Is there some way we can figure out the period and size of a binary star orbit without having to know the distance?

Suppose that, instead of taking an IMAGE of a binary star (as we did above), we instead acquire a SPECTRUM. As each of the stars moves in its orbit, it sometimes comes towards us, and sometimes goes away from us. That causes a Doppler shift in the positions of its spectral lines.

It's obvious that we can use the shift in the wavelength of lines to determine the PERIOD of the orbit ... but how can we calculate the separation between the stars?

Well, the size of the shift in wavelength is related to the speed of the object towards us or away from us:

(change in wavelength) v

------------------------ = -------

wavelength c

And if we know the speed of the object, and the time it takes to make one revolution, we can figure out how big its orbit must be. The total distance around the orbit must be equal to (the speed of the star) multiplied by (the time it takes to complete one orbit).

Q: The spectrum of star HD 11233 shows a shift in the position of the Hydrogen-alpha line from 6561 Angstroms to 6565 Angstroms over the course of 58 days. What is the size of this star's orbit around its companion?

There's good news and bad news about spectroscopic binaries.

So spectroscopic binaries are nice ... but they usually leave us with only lower limits on stellar masses. Is there any way to get a real, honest-to-goodness measurement instead of a limit?

If a binary star happens to have an orbit which is edge-on as seen from the Earth, then the stars will take turns passing in front of each other as they revolve.

If we measure the brightness of the system over and over again, we will see periodic variations due to the eclipses; we call these systems eclipsing binary stars.

Now, the great thing about these systems is that they get rid of that uncertainty in inclination: eclipsing systems must have orbits which are VERY close to edge-on. If we can measure the shift in the spectral lines of stars in an eclipsing binary star, then we have

And that's enough information to calculate the mass of the two stars accurately.

But wait -- you also get free bonus information from eclipsing binary stars! If you look carefully at the shape of the light curve, you can determine the SIZE of each star.

It seems obvious how to get the size of the bigger of the stars ... but how can you get the size of the smaller one? Think about this for a moment ....

The key is to watch the GRADUAL decrease in the combined light of the system as the smaller star passes in front of the larger star ...

If you can figure out how long it takes for the smaller star to move from "just starting to cover some of the larger star" to "now covering as much of the larger star as possible" -- in astronomical terms, how long it takes to move from the start to end of ingress -- and if you know the speed with which the stars are moving around each other, then you can calculate the size of the smaller star, in real units like meters or miles.

The bottom line is that eclipsing binary stars provide us with most of our information on stellar mass and stellar size. They are extremely valuable "laboratories" for astronomers, which means that people are always looking for more of them.

So, we can measure the masses of stars. So what? Well, remember the HR diagram? Most of the stars fall onto a diagonal line running across the diagram, called the Main Sequence. What happens if we mark masses on the HR diagram?

Aha! Mass must have some connection to the temperature and the luminosity of stars.....

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

Copyright © Michael Richmond.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.