Animation courtesy of John Reid, Ufo karadagli and Wikimedia

One of the main reasons that physicists have adopted radians as an angular measure, instead of degrees, is the ease with which they allow one to convert between linear and angular measurements.

Consider a wheel with radius R = 1 m. We place the wheel on the ground at position x = 0, and roll it forward by one full revolution.

Animation courtesy of

John Reid, Ufo karadagli and Wikimedia

Q: What is the LINEAR displacement of the wheel x? Q: What is the ANGULAR displacement of the wheel θ?

Suppose we choose a larger wheel, one with radius R = 3 meters. If we roll this larger wheel forward by one revolution,

Q: What is the LINEAR displacement of the wheel x? Q: What is the ANGULAR displacement of the wheel θ?

Let's make a completely general case: we'll choose a wheel with some arbitrary radius R. If we roll this wheel forward by one revolution,

Q: What is the LINEAR displacement of the wheel x? Q: What is the ANGULAR displacement of the wheel θ?

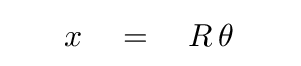

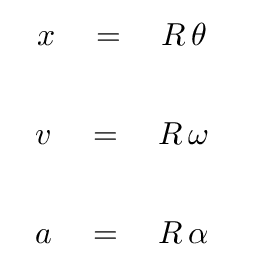

It turns out that we can write a general formula which converts some angular displacement θ into a linear displacement x. The conversion factor is simply the radius R of the rotating object.

Q: Are the units the same on both sides of this equation?

We can only make the units match in this sort of conversion if we declare that radians aren't really units; or, if they are units, they are allowed to appear and disappear in certain equations.

Exactly the same relationships exists between the velocity-type quantities, and between the acceleration-type quantities.

"Big Ben" is a very large clock at the top of one of the towers of the Westminster Palace in London. The minute hand is 4.3 meters in length.

Image of Fremantle Ferris Wheel courtesy of

Viator.com

The Ferris Wheel in Fremantle, Australia, is about 10 m in radius. After people get on, the operators start the motors, and the wheel begins to turn. As it speeds up from rest, the cars accelerate at a = 1.2 m/s2.